This blog is second in the series on the key findings and recommendations of the recently concluded Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) Indonesia survey. It elaborates on one of the key recommendations of the ANA survey which is to allow third parties to set up and manage agent networks. The first blog “A First Look at Indonesia’s Emerging Agent Network” summarised the key findings of the ANA survey.

Indonesian agent networks are growing fast but suffer from service-level issues

The ANA study in Indonesia highlighted the duopolistic nature of agent networks in the country. The two largest service providers, Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI) and Bank Tabungan Pensiunan (BTPN), account for 80% of the digital financial services (DFS) agents’ market presence. Not surprisingly, BRI, Indonesia’s largest commercial bank, accounts for 51% of the agents in the country.

The number of agents managed nationally by individual service providers in Indonesia is astonishing. BRI operates the widest and largest network of banking offices in Indonesia with more than 10,500 offices including branches, sub-branches, cash offices and BRI units. These offices, in turn, manage a network of more than 215,000 DFS agents.[2] Other leading service providers also manage large networks of agents – while BTPN has > 200,000 agents, Bank BNI has >60,000 agents.

These agent numbers are much higher than other networks managed by individual service providers in other more mature DFS markets such as India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. While service providers like BRI can afford to manage such a large agent network, for most other service providers that do not already have an extensive distribution network, building or managing large agent networks is not very efficient. The cost and resource requirements to manage such large agent networks can be exhausting. Most providers, therefore, struggle to efficiently service and manage expansive agent networks. A number of critical service issues in this context have emerged.

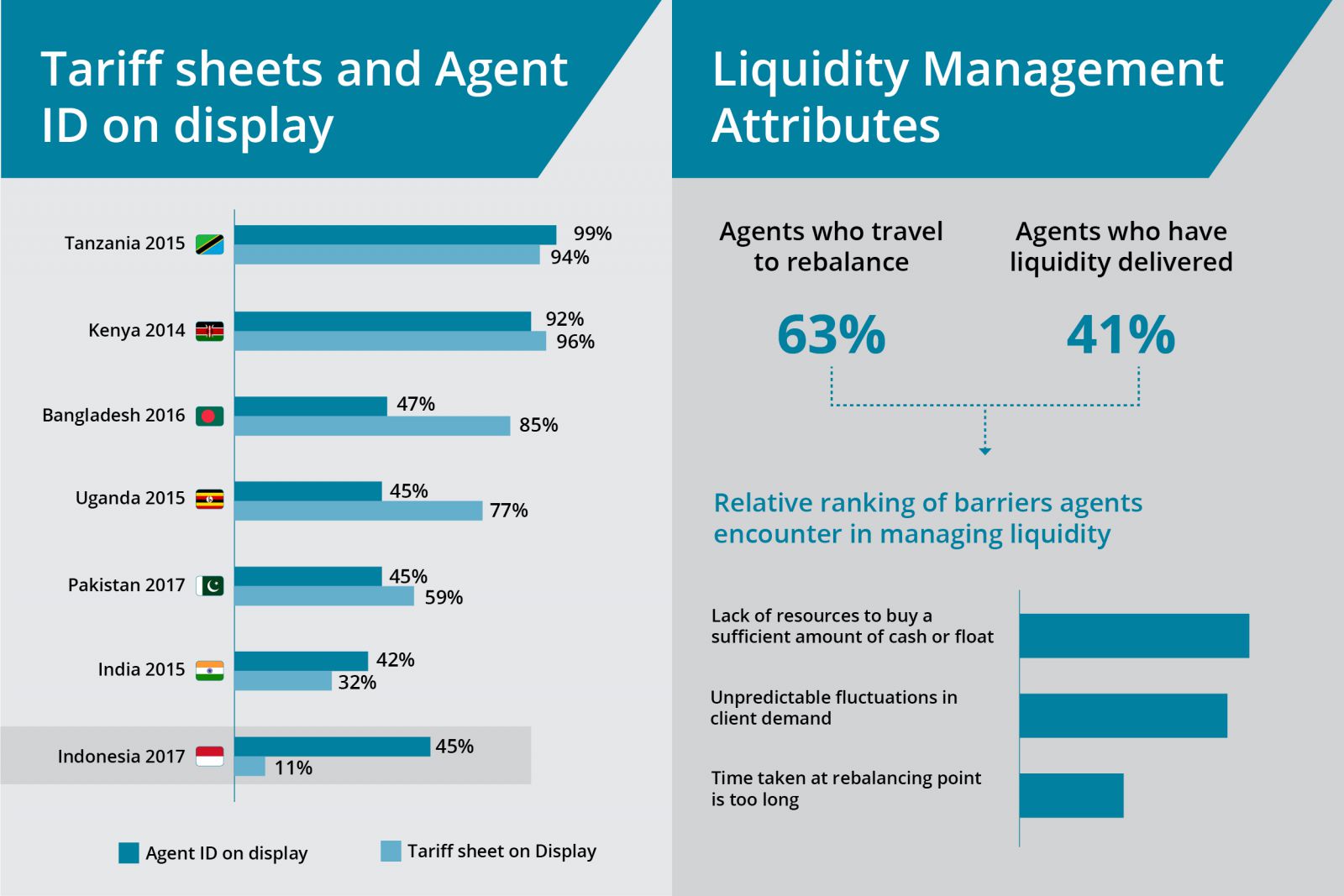

The ANA survey highlights that despite low transaction volumes, Indonesian agent networks rank relatively low on several aspects related to branding, liquidity management, and training. As far as outlet branding is concerned, only 11% of agents in Indonesia display tariff sheets while only 45% display agent IDs. The liquidity management practices are still rudimentary and most agents (63%) must travel outside to their respective link branches to rebalance float. Unpredictable fluctuations in client demand and time taken at the rebalancing point are some of the key barriers related to liquidity management that agents experience.

The present reach of DFS agents does not extend deep into rural areas either, as 85% of them operate within a distance of 15 minutes from their nearest bank branch. The key reason for such a limited presence is the inability of the providers to manage agents that are far away from their physical distribution establishments or branch office.

Third-party ANMs have been successful in many other markets and have performed multiples roles

In other more mature DFS markets, third-party agent network managers (ANMs) have played a critical role in helping providers scale up and manage their agent networks efficiently. However, the regulators in Indonesia currently prohibit third-party ANMs for individual non-registered agents. They allow service providers to partner with registered entities that operate franchise outlets to offer DFS services, such as Alfamart and Indomaret. However, the capability of such entities to offer DFS is inadequate given their limited reach in the rural areas.

As the DFS market matures in Indonesia with providers offering more complex products and services, the service levels of agents will be critical to ensure the success of digital financial inclusion initiatives in the country.

The global success of third-party ANMs has been well-researched and documented. Their role in agent management can be as varied. ANMs range from airtime distributors, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) distribution agencies, transport companies, and even specialised or dedicated agent management companies. In India, ANMs have been a critical component of the success of DFS in the country. The ANA survey in India highlighted that the third-party ANMs currently recruit and manage 65% of DFS agents. Similarly Banco do Brasil, one of the largest commercial banks in Brazil, has partnered with more than 50 ANMs to manage a network of its DFS agents.

.jpg)

The services of ANMs have benefitted even the non-banks, including mobile network operators who already have a large network of airtime distributors. Kenya’s Safaricom independently owns and manages less than 20% of M-PESA agents, while multiple third-party ANMs manage the rest. The providers have used services of third-party ANMs in a variety of ways. These include recruiting, training and on-boarding agents, below the line (BTL) marketing support, liquidity management, monitoring, supervision, and research and strategy. In many markets in South Asia and Latin America, ANMs have also provided innovative technology solutions to the banks to facilitate DFS products and supervise agent activity. The opportunities and scope of services that ANMs can offer in the Indonesian DFS market are immense, given the current situation and future potential of agent networks in the country.

Regulatory concerns on the role of ANM are valid but can be resolved through appropriate risk mitigation protocols

MicroSave’s interactions with DFS stakeholders in Indonesia have revealed that regulators have concerns about involving an intermediary between the bank and the agents. Their key concerns are the capabilities of ANMs to ensure high-quality customer service, training to agents, customer protection, and risk management at the agent level. While these concerns are valid, best practices to manage risks arising out of such arrangements have emerged in other countries. Key among these is to make the service providers accountable for all activities performed by the third-party ANMs on their behalf. This ensures that service providers conduct proper due-diligence in selecting appropriate entities, and introduce sufficient internal monitoring and control measures to supervise the operations of the ANM.

For example, in India, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) guidelines for banking agents allow a broad range of entities, including individuals and registered entities, to become banking agents and also allows the agents to appoint sub-agents. However, the guidelines demand that the bank be accountable for meeting the statutory requirements – know your customer (KYC), anti-money laundering (AML) and combating of financing of terrorism (CFT) – and customer protection at both the agent and sub-agent levels. Specifically, RBI makes banks accountable for ensuring transparency of commissions, customer data confidentiality at the agent or at the sub-agent level, training of agents, types of products and services offered by the agent, etc. These regulations have resulted in the emergence of specialised ANMs in India that manage the bulk of the agents for the banks. This has helped the banks to increase their outreach, especially in the remote, rural areas.

Banks in Indonesia already work with some third-party agencies to sell credit cards and manage ATMs on their behalf. In all these activities, there is clear responsibility of the parent bank in ensuring customer protection. Managing agent networks can similarly be outsourced. The key point here is to give service providers the flexibility in setting up the branchless banking business that is suitable for them. Service providers with an already wide branch presence may not see the utility of a third-party ANM, but other providers may feel the need and enabling regulations can nudge them to participate in the branchless banking programme.

The Indonesian payments market is dominated by dedicated bill payment operators called Payment Point Online Bank (PPOB). The PPOBs provide their services through thousands of agents. Given their core strengths in managing large-scale payments distribution networks, PPOBs can potentially support efforts of a service provider in developing agent network by providing following support: agent on-boarding, training, monitoring and supervision.

Conclusion

The potential of third-party ANMs is immense in a relatively young DFS market like Indonesia. ANMs can spur technological innovations in servicing agents that can improve agent viability and customer service levels. Allowing providers to partner with ANMs will encourage more providers to contribute to the financial inclusion vision set by the Indonesian government. ANMs will positively disrupt the Indonesian DFS landscape, and make it more competitive and, as a consequence, more innovative.

[1] Jabodetabek - Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, Bekasi (Cities under Greater Jakarta)