Digital Financial Services (DFS) emerged in Indonesia in 2007, with e-money services targeted at the middle income and affluent segments rather than the unbanked and underbanked masses. In 2014, regulators allowed banks and e-money providers[1] to use individual agents, paving the way for the emergence of agent networks. Since then, financial inclusion has become an important development goal of the Indonesian government, with DFS delivered through agents being its key driver.

MicroSave/The Helix Institute of Digital Finance conducted the first round of Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) Indonesia research in 2014 when the branchless banking regulations had just been rolled out. Based on qualitative agent interviews, the research highlighted nascent attempts by providers to develop agent networks and issues related to agent selection/training and monitoring systems. In 2017, MicroSave completed the second round of research, which was a large-scale, nationally representative quantitative survey of 1,300 DFS agents. The study aimed to inform relevant DFS stakeholders on the progress and challenges of agent network development. It would also inform stakeholders on the opportunities to further expand and improve efficiency and quality of service delivery via this channel for digital financial inclusion in the country. This blog summarises the key findings of the ANA survey.

Two Service Providers Dominate the Market Presence

In three years, Indonesia has seen a rapid expansion of DFS agent networks. According to OJK data, over 400,000 DFS agents are serving over 10 million DFS accounts in the country. Despite such high growth rates, agent and customer dormancy remains high. MicroSave estimates more than 30% of DFS agents and 30%–55% of DFS accounts are dormant.[2] The agent network in the country is relatively young – 75% of agents have been in the DFS business for less than two years. Indonesia also happens to be the only ANA research country in Asia where women agents outnumber their male counterparts – 59% of DFS agents are women.

While more than 20 DFS providers currently offer DFS services, two banks – Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI) and Bank BTPN account for 80% of Indonesia’s DFS agent population. With a staggering 63% market presence, BRI is more dominant in Jabodetabek (Greater Jakarta) and rural areas but has a more modest presence (44%) in urban areas outside Jabodetabek.

Agent Network is Exclusive and Non-dedicated

In line with the existing regulations, virtually all (97%) of Indonesian agents are exclusive, serving only one service provider. However, one-third (33%) of exclusive agents expressed interest in serving more than one service provider. A common motivation for mandating exclusivity is to give the regulator clarity on who is responsible for agent training and monitoring, customer grievance mechanisms, and consumer protection. This appears to be the case in Indonesia. Nearly all agents (96%) are non-dedicated, meaning DFS is an add-on to their existing line of business. Non-dedicated agents are significantly more profitable compared to their dedicated counterparts. Only one-third (38%) of dedicated agents can break even or make profits from their DFS activity, compared to 80% of non-dedicated agents. This is understandable given that the DFS market is nascent, transaction volumes are low, and regulations mandate exclusivity.

Service Offerings are Diverse, but Account Opening is Deprioritised

Although expanding access to a bank accounts is the cornerstone of the national financial inclusion strategy, at the moment, only 28% of agents offer account registrations. A cumbersome account opening process, ineffective incentive systems, and a lack of customer DFS awareness hinder wider registration offering. Similar to markets like Pakistan and Bangladesh, Indonesia is largely an Over-The-Counter (OTC) market, where money transfer and bill payment transactions dominate. Low average cash-in values (USD 8), as opposed to money transfer (USD 30), indicate that providers have yet to devise use-cases that would compel Indonesians to keep and use the money in their digital wallets/accounts.

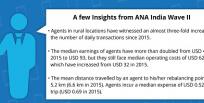

Transaction Levels and Profitability is the Lowest Among all ANA Countries

Indonesian agents conduct a median of four transactions per day, the lowest amongst all ANA research countries. Agents in other OTC markets, such as Pakistan (15), Bangladesh (30), and Senegal (35) transact more. Exclusivity requirements combined with the nascence of the DFS market largely explain the low transaction volumes. However, agents in the Jabodetabek area are the busiest, conducting a median of 10 daily transactions, which is a figure comparable to agents’ transaction volumes for a single provider in Pakistan. This pattern is hardly surprising since the early adopters of DFS usually live in big cities. The agents in rural and non-Jabodetabek urban areas conduct five and three median daily transactions, respectively. The low transaction volumes result in low agent profitability. The median monthly profits from the DFS business is USD 6, significantly lower than in Senegal (USD 120), Kenya (USD 77), Bangladesh (USD 57), and Pakistan (USD 43). Surprisingly, despite low profitability, half of the agents are satisfied with their earnings from the DFS business, while 91% want to remain in the business for another year.

Internal Teams from the Providers Manage the Agents

Since regulations currently prohibit partnerships with third-party agent network managers, most service providers use in-house teams to recruit, train, monitor, and supervise agents. Strategies for agents monitoring and supervision varies: larger banks with deep rural presence manage agent networks through regular bank branch staff, while other providers have appointed dedicated teams to manage their agent networks. Despite providers’ efforts, most agents reported that they are only “somewhat” satisfied with provider support services.

Three-quarters of agents reported being trained within the first three months and virtually all the agents are trained by service provider staff. Agents in the Jabodetabek areas are less likely to receive training compared to their rural and non-Jabodetabek urban counterparts. The majority of agents (67%) depend on support staff to address grievances. Only around a third of agents use WhatsApp and call centres for support. Agents receive infrequent and ad-hoc support visits from the provider staff. Nearly half of agents (43%) do not receive visits at all, which translates into low product awareness, low compliance, and inconsistent customer service. As agent networks evolve and continue to grow, the processes of recruitment, monitoring, training and liquidity management challenges will likely intensify. Allowing service providers to partner with Agent Network Managers (ANMs)/Aggregators will help to scale agent networks effectively and avoid overburdening bank staff or bloating agent network servicing teams.

What’s Next?

Agent networks in Indonesia are nascent but evolving. The recent government push to digitise payments (G2P) can propel agent networks and drive the demand for customer registrations and consequently transactions. The DFS community can complement government efforts by investing more in consumer awareness drives to further boost the uptake and usage of DFS services. The next blog in this series will highlight measures that service providers and regulators can take to stimulate the DFS market along with best-practice from more mature markets.

[1] In Indonesia, the DFS offering fits in two broad categories: ‘Laku Pandai’ basic savings accounts, only offered by the banks and ‘Layanan Keuangan Digital’ (LKD) e-money services, offered by both banks and non-bank.

[2] Agent dormancy estimates are based on the mapping exercise during data collection. While there is no publicly available data on customer dormancy in DFS, based on internal MicroSave analysis, it is estimated that customer dormancy in DFS ranges anywhere between 30%–55%