Agents are deemed the lynchpin of any successful digital finance (mobile money or agent banking) roll-out. A plethora of literature has been written about the role they play in building successful and sustainable digital finance businesses. Less attention has been paid to the critical work of Master Agents who constitute an important, if not crucial, element in the agent-based distribution network.

Popularised by Kenya’s M-PESA model, simply put, a Master Agent is a person or business who has been contracted by a digital finance provider to manage a number of its retail agents. Master Agents play an important role in helping with financial and operational tasks, such as selecting and onboarding agents, training them, keeping them liquid and, in some markets, ensuring compliance on the ground. However, in reality, defining a Master Agent, understanding their roles and responsibilities, and the benefits and challenges they bring to a roll-out, is both confusing and complex. This first blog highlights and attempts to untangle some of these complexities.

Who are Master Agents?

The wide range of terms used to describe Master Agents is a source of confusion in the industry. Although both consultants and donors refer to this layer in the distribution channel as ‘Master Agents’, providers in different markets use a variety of terms while referring to them. These range from Aggregators in Kenya to Super Agents in Nigeria, and from Super Dealers in Tanzania to Distributors in Bangladesh. In some markets, mobile network operators (MNOs), such as EasyPaisa in Pakistan, have built their agent networks on top of their existing GSM distribution network. These GSM distributors, referred to as Franchisees, are employed to manage a number of retail agents and, therefore, undertake roles similar to those of Master Agents. Under this model, however, only pre-existing GSM distributors serve as Franchisees. They should, therefore, be seen as distinct from Master Agents, who may be engaged in a variety of other business activities, rather than mere GSM distribution.

Figure 1 and 2 highlight the distinction between theMaster Agent and Franchise models

Figure 1

Figure 2

Master Agents are usually selected by providers based on their financial muscle and distribution expertise. Their commercial activities range from airtime brokerage and FMCG distribution, to retail of hardware or ownership of public transport buses. Airtel Uganda and Eko, a third-party specialist in India, use Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) distributors, such as Unilever stockists, and GSM dealers with existing retailer networks as their Master Agents. Similarly, Islam Bank Bangladesh Limited (IBBL), before switching to a shared agent model , used telecom airtime distributors as Master Agents. Both providers and regulators tend to set minimum start-up capital requirements for Master Agents. For example, Airtel Uganda requires that Master Agents must be registered businesses with fifty million Ugandan Shillings (US$16,750) in capital. The Central Bank of Nigeria regulates that Master Agents must have a minimum Shareholders' Fund, unimpaired by losses, of 50 million Naira (US$15,860). These prerequisites are kept to ensure that Master Agents can assist when liquidity needs arise, as well as play a key role in expanding the agent network.

Roles and Responsibilities

As with their titles, the roles and responsibilities handled by Master Agents also vary from provider to provider. At a fundamental level, Master Agents are employed to manage a number of retail agents. In Nigeria, Central Bank regulation requires Master Agents to manage a minimum of 50 agents. In Kenya there is an informal rule that M-PESA Master Agents should manage a maximum of 200 agents under one business name, ideally spread across a large geography to ensure better float management. In reality, they are able to register multiple businesses, and therefore manage far beyond this number

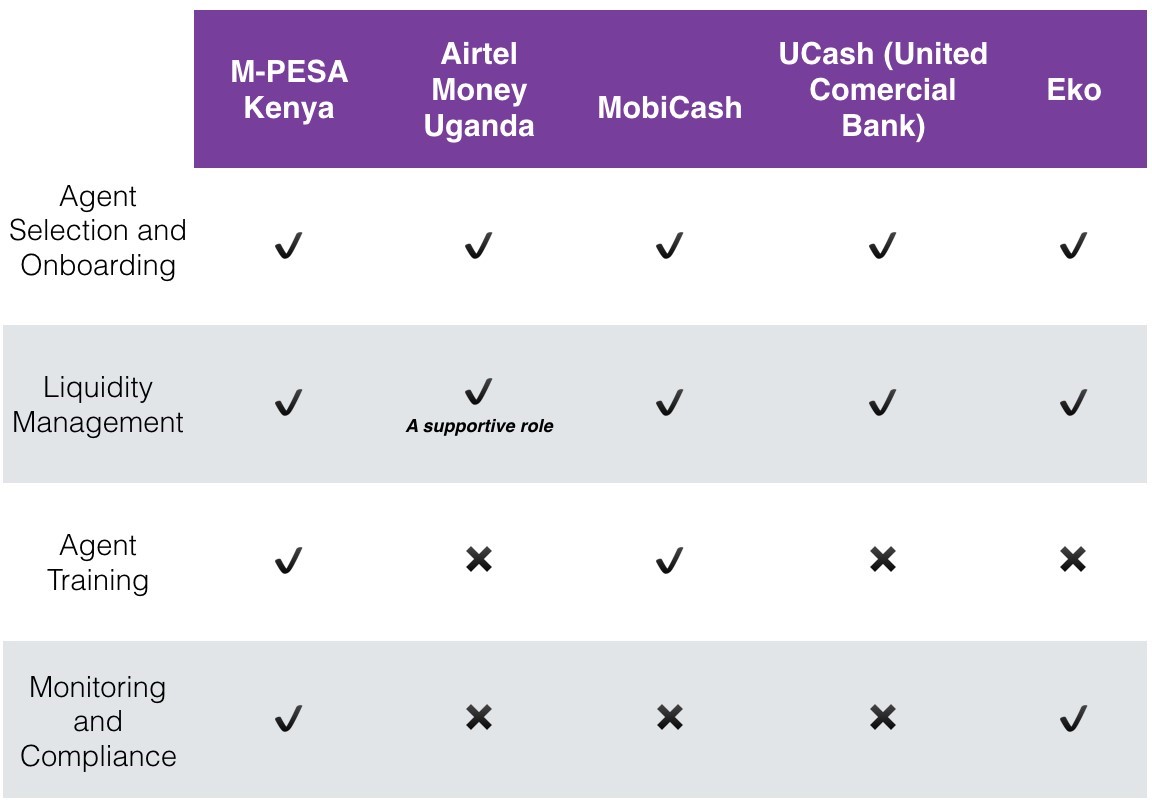

Mas and McCaffrey’s 2015 paper on digital finance distribution strategies, and data from in-depth interviews conducted by MicroSave, highlight the lack of uniformity in what Master Agents do for different providers (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Master Agent Roles Across Providers

Across all providers, it is the responsibility of Master Agents to select agents and on-board them, in order to assist with a roll-out's speed to scale. Liquidity management is also commonly assigned to Master Agents. In Bangladesh, Master Agents employ runners to offer doorstep liquidity to their agents. Eko in India and M-PESA in Kenya manage their agents’ liquidity through a back-end portal. On the other hand, the matter of who is responsible for monitoring and training agents is a contentious one. While some see agent training as a core responsibility of the Master Agent, others view it as that of the provider. In 2013, 41% of agent training was conducted by Master Agents in Tanzania. This was compared to 10% in Kenya in 2014. Due to misaligned KPIs and incentives, GSMA regards Master Agents as inadequate resources for training agents.

The monitoring of agents is often left to the provider or a third party organisation. In Kenya, however, monitoring is central to M-PESA’s Master Agent model. Although Safaricom uses Top Image, an Agent Network Management Agency, to help audit their monitoring and compliance, Master Agents are encouraged to play a complementary role and are often held accountable if things go wrong. In one interview a M-PESA Master Agent highlighted how he was held responsible when one of his agents was involved in a fraudulent activity. Master Agents believe that Safaricom is using them as an insurance policy and a buffer to isolate the company from fraudulent agent activities.

What benefits do they bring to roll-outs?

The unique selling point of Master Agents is that they enable agent networks to scale up faster. By outsourcing the management of operational matters to Master Agents, providers are able to speed up the overall scale of the digital finance business. Master Agents have also helped providers expand into hard to reach areas in which they previously lacked presence. M-Sente Uganda implemented Master Agents into their distribution model to help them spread into more rural areas of Uganda. Master Agents are also seen to play an important role in keeping agents liquid. GSMA research in Chad found that Master agents were a critical liquidity line where 84% of successful agents were operating in the absence of a bank.

What challenges do they pose to a roll-out?

Although little upfront investment is needed to introduce Master Agents into a roll-out, it does make the system more expensive. Master Agents are typically paid a 20% share of agent commissions. Combined with retail agents' 80% share, these commissions are believed to consume 40-80% of mobile money revenues, posing a huge operational cost for providers. In Tanzania, in a bid to reduce this operational expenditure, M-PESA terminated all of their Master Agent contracts enabling them to renegotiate the 30% commission they were paying to Master Agents.

Additionally, although outsourcing management to Master Agents enables providers to scale more quickly, it cedes some of the provider’s control over the network. This can raise concerns with regulators and may affect the offering of more complex products. This added management level between the provider and end customer also results in monitoring having to take place at an additional level. Most challenging, however, is the lack of best practices, and understanding of the evolving role of Master Agents. While digital finance businesses are maturing, there appears to be little literature on how the Master Agent model evolves with it. A second blog will try and explore some of these evolutionary questions.

Annabel has recently completed a Masters Degree in Development Studies at SOAS in London, UK. She is currently working as a freelance consultant on various digital finance / mobile money projects. Previously Annabel worked as a Senior Manager in the Digital Financial Services Department at MicroSave, based in Nairobi Kenya. At MicroSave, Annabel worked on The Helix Institute of Digital Finance project, where her work focused on providing in-house technical assistance consultancy to digital finance providers, training providers on different technical areas of digital finance, and supporting the development of thought-leadership publications.