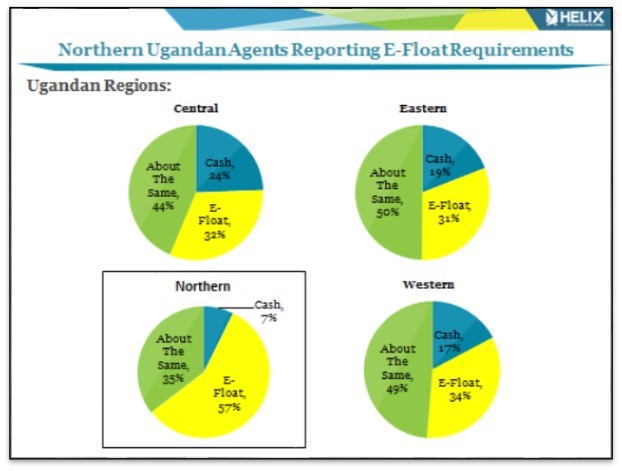

It’s a common belief that agents in rural regions need more cash than e-float to meet the demand of their customers, while in urban areas cash-in and cash-out transactions balance themselves out. The 2013 Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) Uganda Country Report revealed that more than half of agents in Northern Uganda (57%) require more e-float than cash. As Northern Uganda is predominantly rural, this finding is extremely intriguing.

High demand for e-float implies that customers are conducting more deposits than withdrawals at agent outlets. In Northern Uganda, 43% of households live below the poverty line—two times the national average—therefore one would expect this region to be a net recipient of domestic remittances. What makes Northern Uganda unique in the unconventional demand for e-float from other rural regions?

Source: The Helix Institute of Digital Finance, Agent Network Accelerator Uganda 2014

The Agriculture Factor in Northern Uganda

Research conducted in Northern Uganda revealed that investments in and proceeds from agriculture activities has increased the amount of money in circulation within the ecosystem which has in turn created opportunities for mobile money transactions—such as smallholder farmers engaged by large, commercial farms. In fact, mobile money agents in Northern Uganda report that they experience high demand for e-float during the months of the two harvest seasons (July to August and November to December) when traders and farmers earn high revenues.

Traders and farmers in Northern Uganda seem to be moving closer to digitizing the agricultural value chain. Unlike other agricultural regions in the country, Northern Uganda has dedicated value chain players (such as the Sorghum Value Chain supported by Nile Breweries). Traders, who play a key role in this value chain, make most of their purchases to their suppliers in the region and even across the border in Congo and South Sudan using mobile money.

Traders choose to digitise their payments because digital payments are a faster, convenient and cheaper means of purchasing supplies than physically travelling to Kampala or outside the Northern Region. They also choose to employ digital payments to increase safety against theft, robbery or fake currencies. It seems that for traders mobile money is a trusted medium for bulk merchandise payments which has resulted in the high level of deposits into their mobile money accounts, and thus agents’ need for more e-float than cash.

Further, paying suppliers is not the only reason agents experience a high demand for e-float. As a result of the income earned from the harvest, traders and farmers deposit money to their mobile wallet accounts. With an estimated 0.2 formal bank branches per 10,000 persons, most of which are located within urban centres (Lira, Gulu, Arua), Northern Uganda has the lowest bank penetration rate in the country. Mobile money agents are accessible and mostly at their doorstep. As a consequence, people store money on their e-wallets as the best option available. Agents note that customers make payments for school fees and send pocket money to their children, as well as remittances to relatives and friends outside the Northern Region.

How Do Agents Cope?

An illiquid agent impacts his/her ability to meet customers’ demands and can hurt an agent’s business. In discussion with agents in Northern Uganda, while they understand the cyclical swings in e-float demand associated with the agricultural/harvest seasons, maintaining a sufficient amount of e-float remains a challenge to rural agents. This is because they lack the appropriate capital, resources, management techniques and at times willingness to invest in their mobile money operations during the planting season.

We interviewed agents who frequently borrow e-float from other agents; an innovative coping mechanism which we also witness in Tanzania. Whilst this is encouraging, these informal management systems can put pressure on the lender, and would benefit from making this arrangement more formalized.

We found that agents carry a small amount of capital for their mobile money operations and thus run out of e-float more often, resulting in the need to rebalance before the next transaction. In fact, in some cases non-dedicated agents often have to choose between their mobile money and parallel businesses when it comes to cash management, mostly during the planting season (when farmers tend to their land). During this time period, agents choose to keep more cash than e-float as they would rather speculate in their parallel business. An illiquid agent can lead to poor customer service such as denying a customer’s transaction, or forcing a customer to split their transaction—which increases both their transaction fee and the time a customer spends to transact.

What Can Providers Do To Help?

The need for e-float in Northern Uganda highlights the importance for digital financial service providers to understand both the needs of their rural customers as well as the liquidity management challenges and coping mechanisms of rural agents. While we understand that liquidity management in rural areas is complex, based on our research with agents, we recommend offering the following services to help agents overcome e-float shortages.

Provide float on credit: Some master agents in Northern Uganda provide e-float on credit. One master agent interviewed provides a 30-minute e-float credit to his agents by sending a float runner to collect the cash. If within 30 minutes the cash isn’t received, the line for the agent is blocked. This indicates an opportunity for structuring an e-float loan product. Access to a sustained flow of e-float through credit financing will enable agents to serve their customers better and build their loyalty.

Develop a reward structure for agents who are inclined to save money than having e-float at disposal: Agents in Northern Uganda use their till as a safe way of banking their business earnings and during the low agricultural season they invest in their parallel business as they weigh between the mobile money commissions and this other business. Providers can reward agents who increase their e-float held during the harvest period, so as to ensure that they can serve customers and thus grow their business.

In Northern Uganda, agents’ and customers’ float requirements indicate that P2B and B2B payments are growing and are linked to their agricultural livelihoods. The mobile money use case in rural Uganda seems to be slowly evolving from domestic remittances to payments and deposits. This implies that practitioners will need to understand triggers for such payments, such as economic seasonality and design practices that suit customers’ and agents’ liquidity needs.