Ugali is cornmeal porridge and a staple of the Kenyan diet; it is as Kenyan as M-PESA. Last time my mother was making it, she ran out of cooking gas and texted me frantically to send her money so she could buy gas and finish cooking dinner before it got soggy. I ran to the M-PESA agent near my office, but they did not have float, and then ran from agent to agent trying to buy float, until the ugali had long become uneatable. If you ask any Kenyan they can tell you their own harrowing tale (some much less funny) about trying unsuccessfully to conduct a transaction with an agent due to float issues. Further, recent research like the Intermedia Kenya Wave 1 FII Tracker Survey on the customer experience with digital finance agents and The Helix Institute’s Agent Network Accelerator Survey - Kenya Country Report (2013) highlights this as among the top three issues hindering transactions.

Agents without float are perennially frustrating for providers who are constantly making new partnerships and products to bring the amount of time needed and cost incurred in rebalancing down. The Helix Institute research from across East Africa shows that agents report that rebalancing is fairly quick and easy, so the question remains, what is prohibiting agents from carrying more optimal levels of float? Given my personal frustration and the mounting evidence of this as a systematic issue I set out to interview 50 agents in Kenya as to what was causing this problem.

Some of the answers are quite surprising and necessitate using a behavioural science lens to better understand how agents think about profit optimization and float management. In fact, in some instances, the agent actually has float, and is refusing to do the transaction for other reasons. Understanding these mental frameworks will help providers to better address the quality of customer service their agent networks are providing.

Agent Transactional Revenue Honing

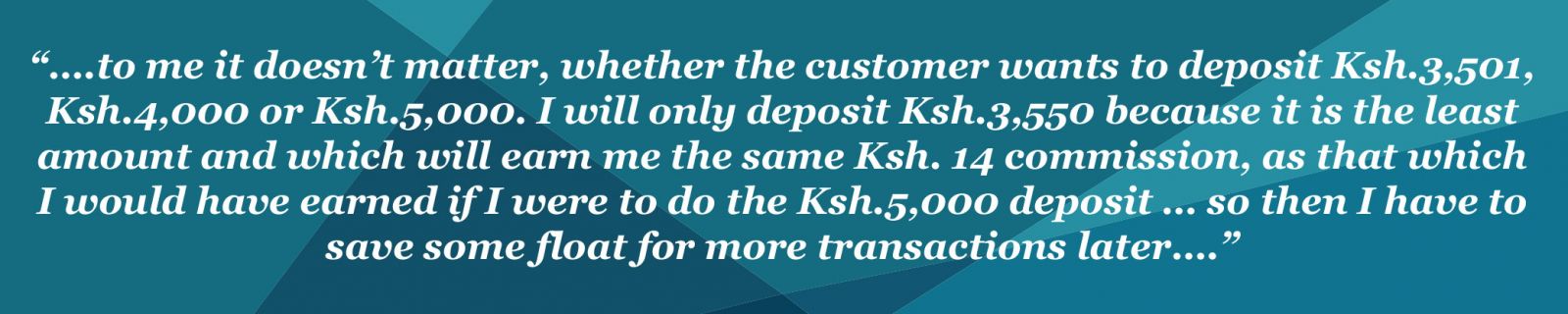

Some M-PESA agents choose to target the maximum revenues per transaction instead of the more prudent strategy of maximizing profits over time. The amount of revenue earned is based on the value of the transaction conducted. Values are arranged in tiers so that all values in that tier yield the same amount of revenue. Hence, agents only agree to conduct deposit transactions closest to the tier’s lower limits, informing a customer that that is the maximum amount of e-float they have to transact. For instance, an agent speaking about the value tier from Ksh.3,501 to an upper limit of Ksh.5,000 explained:

Most customers are then left to abide by the amounts quoted by the agents and not fully accessing deposit services that address their needs. Depending on the customer needs, some opt to search for other agents while others end up splitting their deposit transactions through multiple agents. Providers need to better communicate to agents the effects of focusing on revenue maximization per transaction as customers are inconvenienced by the resulting limitations on access to e-float, and makes them prone to completely losing their customers in the long run.

Agent Default Stickiness

There are other agents who opt not to increase the float they hold despite the growth in the demand for digital finance transactions over time. While it may seem simple to decide to invest more in a business that is noticeably growing, the truth is it is not. The proprietor must weigh increasing float vs. all the other invest opportunities they have in the other products in their store. Even if they did decide float was a prudent investment, how much more should they buy and how might that affect the risk of getting defrauded? These fundamental decisions can be complex enough to drive agents to just stick with their default amount – the original amount required by the provider to start their agency business. In which case, agents report rationing the float they have for their most loyal customers. Meaning they will reserve float for regular customers, and deny other transactions even when they have the float to make them.

To address this, providers or master agents may push such agents to grow by automatically increasing the default. There could be percentage growth mandates for agents with clearly defined timelines for instance 20% growth every year, which would aid in determining the progressive defaults over time. Agents also need to be more knowledgeable on risk mitigation and risk reporting to reduce their concerns with facing risk or fraud.

Agent Transaction Pooling

While some agents opt to maximize revenue by transaction, others try to limit volatility in their earnings by forming groups with other agents and pooling their risk. Group members help each other by lending each other small amounts of money to make change for customers, referring customers to each other, and where all the group members are under one master agent, the agents take turns going to the bank branch for rebalancing.

The group support also extends to slow days, when specific agents are not doing many transactions. They will communicate it to the group, and other members, even when they have float, will turn away customers, directing them to the agent needing more transactions that day. This helps ensure that revenues are more reliable on a daily basis for everyone in the group. It also makes sense, since it will mean agents will be much more likely to have in sync needs for rebalancing, which they benefit from doing together as well. Providers must recognize this need for predictable revenue streams, and the gains agents experience from pooling the work of rebalancing, and therefore provide superior solutions for them, or risk having this system persist.

Addressing Agents’ Mental Frameworks

The above are just initial insights, and so while these trends were clearly observed, we are still unclear of the prevalence of them on a national scale. These practices indicate a clear disconnect between the mental frameworks of providers who are trying to facilitate rebalancing and agents who have float and are still denying transactions. Probably the scariest realisation here is providers cannot see these problems on their virtual dashboards, because the agents actually have float, they are just not always willing to use it, and therefore customer service will continue to suffer. These issues highlight the importance of regular agent monitoring and research techniques like mystery shopping that will give better data on the prevalence of these issues, and cost effective solutions to address them.