The success of a branchless banking network is entirely dependent on the ability of its agents to deliver high-quality services to the target market, that are in line with providers’ objectives. Three years ago, the Helix Institute of Digital Finance’s team first set off to study Pakistan’s agent network and inform on its efficiency, providing insights for improvement, as well as highlighting the opportunities for the DFS community. What we found was a fractured, but highly competitive mobile money market. Opportunities for progress were abound, and the DFS community was excited for a future of innovation spurred by the competitive environment.

This year we went back to agents for a second wave of the Agent Network Accelerator study, funded by Karandaaz Pakistan to investigate how Pakistan’s mobile money market has evolved since the previous wave of the study in 2014. This blog highlights the key findings from the study.

Maturing Market

Pakistan has established a large agent network via franchises, where the majority (90%) of agents act as retailers under them. The latest figures from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP)[1] indicate that providers have registered over 360,000 agent tills, although a significant number (approximately 30%) are inactive. New tills continue to be issued, albeit at a slower rate (2%)[2] in the first quarter of 2017 than in the same period last year (13%)[3]. As a result, the network is maturing: in 2014, 40% of the agents were less than a year into operation, compared to just 7% this year.

.jpg)

Despite the evolving market dynamics in Pakistan, the larger providers supported by MNOs continue to dominate the DFS landscape despite offering similar products and models as other players. Telenor Easy Paisa, Mobilink Jazzcash and Ufone Upaisa account for three-quarters (76%) of the market presence, having a bigger share of the agent market presence than the pure bank led operators.

Despite the evolving market dynamics in Pakistan, the larger providers supported by MNOs continue to dominate the DFS landscape despite offering similar products and models as other players. Telenor Easy Paisa, Mobilink Jazzcash and Ufone Upaisa account for three-quarters (76%) of the market presence, having a bigger share of the agent market presence than the pure bank led operators.

Having driven the mobile money revolution in Pakistan, Telenor Easypaisa maintains the largest presence of agents (32%), holding steady at 2014 levels. Meanwhile, Mobilink Jazzcash is catching up to their main competitor. It has expanded its market presence to 30%, with a 7% growth since 2014. Warid’s Mobile Paisa previously had a market presence of 5% in 2014, and so at least some of Mobilink Jazzcash’s growth may be attributable to its absorption of Warid’s mobile money business after the merger.

Commissions battles to win agents and thereby customers led to smaller providers being bled dry. Although their mobile money services are still operating and available, many agent tills for these providers are now dormant due to a lack of demand for their services. The DFS market is poised to become less competitive in the future unless the small providers can reinvigorate their mobile money businesses and reactivate their dormant agents.

Increasingly Shared but Efficient Network

Pakistan is a leader in shared agent networks: both in terms of non-exclusivity[4] and non-dedication,[5] the highest levels of any other market. Virtually all (96%) agents in Pakistan are running parallel businesses, and more than three-quarters (78%) are serving multiple providers, up from 66% in 2014. Only larger providers maintain some level of exclusivity within their networks, which isn’t surprising, as smaller providers recruited agents from the existing networks of bigger players. Agents can invest only a limited amount for float for their business, but high rates of non-exclusivity, mean agents are often serving a median of 3 providers, who must compete for their agents float investment. As a result, those providers facing a higher demand for their services win, especially since commission wars came to an end.

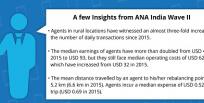

Although most agents are generally small, they are earning reasonable profits (US$149[6]) and are largely satisfied and optimistic, with most agents continuing to see themselves remaining agents for another year. Although profits do seem to be declining since 2014, this could be largely the result of lower commissions from the providers. Another reason is relatively high operating expenses, which are the highest amongst the ANA markets. Liquidity management and delivery systems are also more efficient than previously reported, with the majority of agents now having their liquidity delivered and fewer agents travelling to rebalance their accounts. Most agents also receive regular visits from support staff; a few also access on-demand facilities.

.jpg)

Gradual Movement from OTC to Wallets

Product innovation and diversification are crucial for mass uptake and adoption of mobile money. Although providers seem to be complying with the regulator's push for OTC to wallet transition, they have largely failed to propose valuable use cases for customers to propel registration and regular wallet account use. While agents are offering a broader array of services, OTC transfers remain the modus operandi for the market with 99% of agents performing these transactions, with bill payment coming in second.

.jpg)

More agents now offer wallet registration services, but they constitute only one-third (34%) of the network compared to nearly double that (62%) for MNO agents in Kenya.[7] Agents do not appear to be concerned about the transition from OTC to wallet services, and an additional 46% of agents want to offer this service but have not yet been granted this capability by the providers, which may hinder Pakistan’s progress on financial inclusion strategy, focused mainly on digital account registration.[8] The product offering may be a reflection of the low levels of product awareness on the demand side as agents cite this as a hindrance to registering customers. Ideally, if providers want customers to transition to wallets fully, wallet cash in and out services should be offered universally by agents, compared to just 70% and 69% respectively, offered currently.

Sluggish Adoption of Biometric Verifications

As of June 2017, agents are required to have Biometric Verification System (BVS) machines to verify OTC transactions.[9] These regulations are part of the regulator's initiatives on Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CFT), which has also been credited for lower reports of fraud experienced by agents: Pakistan has one of the lowest rates of agent-reported robbery and fraud among the ANA research countries. However, as mobile money uptake increases, providers will need to ensure their agents are prepared to prevent and mitigate fraud further.

Although providers have begun investing in the transition, they are still falling short, and the rollout appears to be slow and targeted due to the high costs of the BVS machines.[10] More than one-third (38%) of mobile money agents still lack the required BVS machines. Seemingly only better performing and more experienced agents are being equipped – those with average daily OTC volumes of $55USD for agents with BVS machines compared to $44USD for those without them. The absence of verification systems may lead to a downturn in OTC transactions in the short term.

What’s next?

Although the providers in Pakistan have shown some efforts to drive wallet registration and usage and the transition from OTC, they haven’t pushed the envelope far enough, leaving many agents unprepared to register customers. Having provided an overview of the evolution of the DFS agent network, the next blog in the series will explore opportunities and potential strategies to accelerate wallet adoption and thus deepen the mobile money ecosystem in Pakistan by combining insights from the ANA Pakistan study with demand-side research.

For background on the ANA Pakistan survey, data, and reports, please follow this link. The full 2017 Pakistan Report can be found here.

[1] State Bank of Pakistan – Branchless Banking Newsletter – January to March 2017

[2] State Bank of Pakistan – Branchless Banking Newsletter – January to March 2017

[3] State Bank of Pakistan – Branchless Banking Newsletter – January to March 2016

[4] Exclusivity refers to an agent’s choice of providers. If an agent chooses only one provider then that agent is referred to as “exclusive”. However when an agent chooses more than one providers then that agent is referred to as non-exclusive.

[5] Dedication refers to an agent’s choice of business. If an agent choses to only focus on mobile money then that agent is referred to a as a dedicated agent. However, when an agent chooses other businesses e.g. mobile accessories, grocery store, medical store etc then the agent is referred to as non-dedicated.

[6] Median monthly profits - PPP adjusted for 2015

[7] Agent Network Accelerator Study Kenya – 2014 - http://www.helix-institute.com/data-and-insights/agent-network-accelerat...

[8] Pakistan’s Financial Inclusion Strategy – SBP -http://www.sbp.org.pk/ACMFD/National-Financial-Inclusion-Strategy-Pakist...

[9] Branchless Banking Regulations – July 2016 - http://www.sbp.org.pk/bprd/2016/C9-Annx-A.pdf

[10] Estimated cost of a BVS machine is between USD$100 – 150.